Starting from today, Mirror Mirror will have another monthly (or so) appointment. It will be in English and dedicated to Italian (fashion) matters that I believe should become more internationally known—or that already are, but may need an Italian perspective to be further analysed.

This is also a hand towards the international friends who follow me (I see you!) out of mere love and pietas—most of them work in the cultural sector and know the struggle to be heard and read. Thank you, especially to my (very British) friend Kirsty, who translates every newsletter, and is a fine editor of my chaotic Master’s thesis.

And from the chaos, I would like to start this new chapter, since a systemic and violent entropy seems to regulate our everyday life and the politics we have handed to nerds and self-centered and coldly irrational men. My housemate often makes fun of me for my room: from Monday to Friday it’s messy, with books and clothes on the floor, while on the weekend it magically goes back to a psychotic tidiness that no one—and when I say no one, I mean it—has the right to undo, except myself, of course. My wavering attitude towards the place I inhabit is something I can easily recognise in today’s society, especially in politics—which is something way more disgusting than a bunch of dirty underwear on the floor.

I was thinking, in these hard times, how to stem the inconsistency of the relationships, conversations, and actions we are forced into by a society that is more and more divisive, and I remembered this nice book, Estetiche del Camouflage (Aesthetics of Camouflage) by C. Casarin and D. Fornari, on the art of camouflage seen as a form of interaction humans and animals similarly use to survive, either in nature or in the societal jungle. The book analyses how architecture, cinema, and design use this technique, and how camouflage can be seen as a mirror of our ever-changing, post-truth times.

But camouflage can be seen as positive if it can subvert our understanding of reality and make us glide into a way of living we’re not used to. Clothes play a pivotal role in the camouflaging. In our everyday life, the clothes we wear are the battleground where meanings and opinions collide. In our clothes, we hide the parts of ourselves we don’t want others to be aware of—our body and our past, our personality and feelings. But we also use them as a flag to be identified and recognised by our social group, or to stand out in a crowd.

I often think about how what I perceive as beautiful, even low-key basic, can be seen as eccentric by a person who doesn’t have my background or simply belongs to a different class or group and applies different norms to their life. Is my hair weird? Are my trousers too baggy, my nails too long, the way I talk too radical and trenchant? Are my shoes weird? I’ve been thinking about how my look could be more sophisticated, not to express sophistication as a cultural, classist tool, but to convey subtlety. I don’t want my clothes to talk for me; I do love talking and expressing myself.

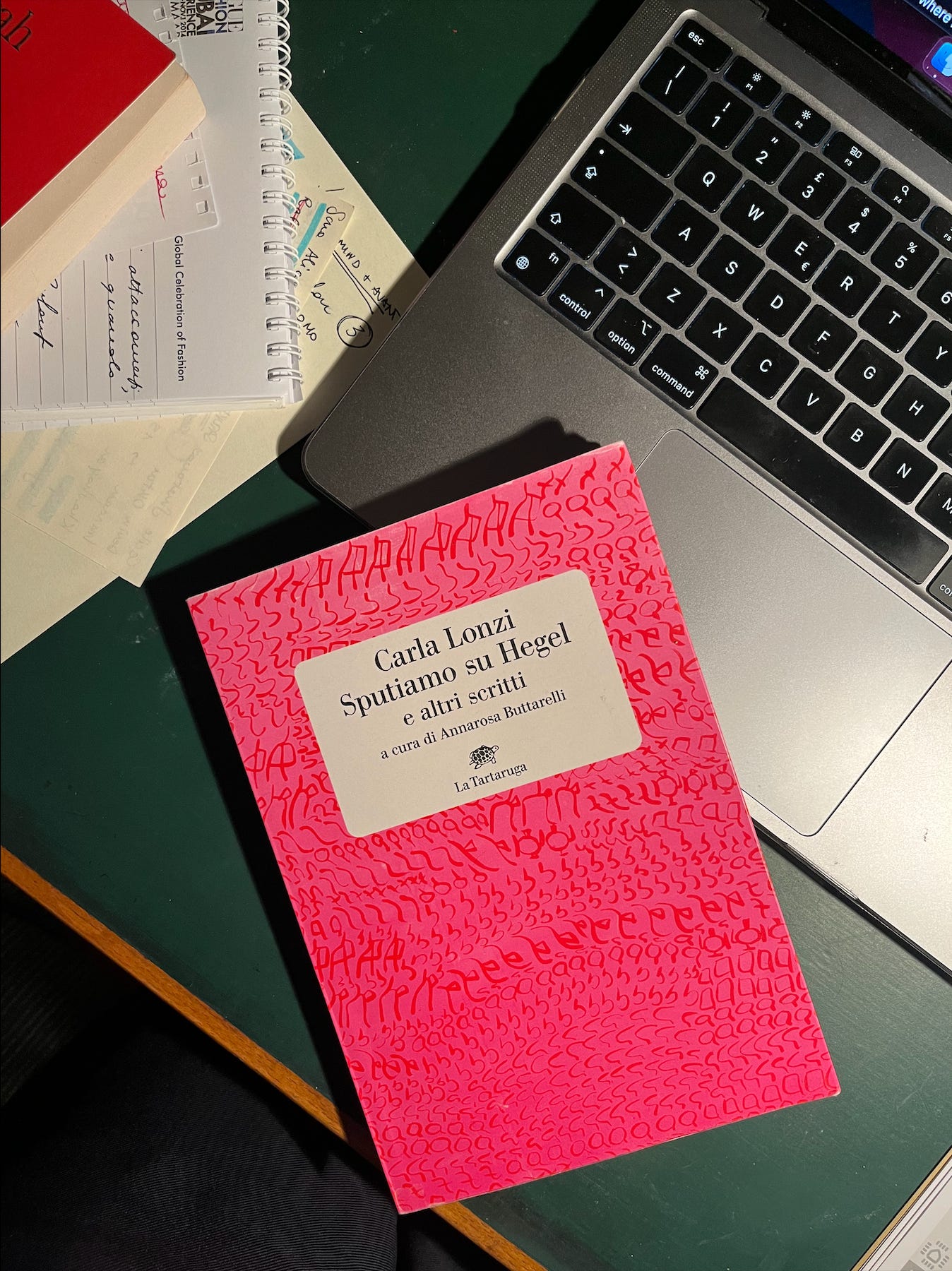

What I want from the clothes I wear is to be a bridge towards those I could never reach with my words. What I ask of them is to be delicate, humble, and subtle. I would love to wear a buttoned-up, straight bonbon pink coat, a quiet luxury beige turtleneck, a velvet skirt, long blue socks, and a pair of white Mary Janes. This is the look of a prude by definition, but these are also some of the most frequently seen elements worn by the feminist theorist and art critic Carla Lonzi, in the photographs we have of her. Lonzi (1931–1982) was the cofounder of Rivolta Femminile, a feminist collective created in 1970. In the same year, she wrote Manifesto di Rivolta Femminile (Manifesto of Women’s Revolt) and Sputiamo su Hegel (Let’s Spit on Hegel), which was republished in 2023 by La Tartaruga.

Lonzi supported separatism (the last point of the Manifesto is “we communicate only with women”), and she was also one of the most significant representatives of the feminism of difference, or rather the type of feminism that believes in the differences existing between men and women, and the necessity of women not conforming to men in a society created by and for them. For Lonzi, women’s freedom would have come through the creation of another set of rules and values, apart from the pyramidal and unsupportive system of men. What Lonzi theorised in the 70s is still considered radical by most people, since she asked to reconfigure society—not only from a gender perspective but as a whole. She wanted a reconfiguration of what structures our society—the culture of work, individualism, and the meaning of success.

For me, it would be a success to be at a random party and talk to a stranger—one of those corporate turtleneck, skinny trousers, Apple Watch guys I would usually find dreadful—and be approached by him, because I wouldn’t be considered horrifying either, thanks to my skirt three centimetres above the knees, my pearls, and the pink eyeshadow. To talk about the weather, the party, the watery drinks we have in our hands. And then queer theory, and intersectionality, and why reformism is not the final goal of feminism and any other revolution, all of this without mentioning these words. To talk about what cannot be named, the uncomfortable, divisive topics, thanks to my mimetic language and, above all, thanks to my clothes.

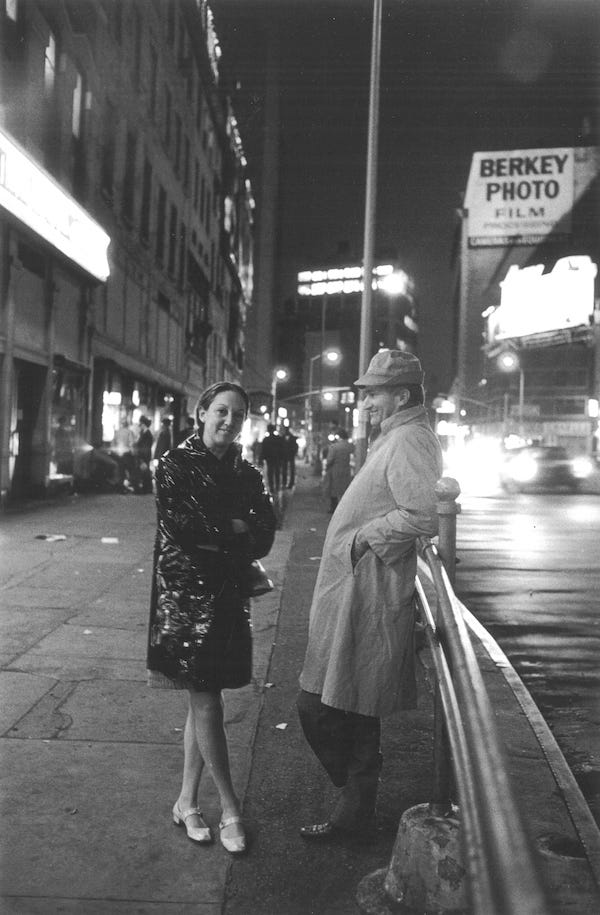

I know that Carla Lonzi’s clothes were probably considered progressive in her time, but what I’d like to do here is an exercise: her thoughts still remain abrasive and urgent, so must her clothes, even if a bonbon pink coat could not be the preferred choice of nowadays conservative girls. There’s an outfit that I like the most because it’s the most exemplary of her way of conceiving reality. Lonzi stands in front of the camera, next to a table covered with bottles and food, with a white shirt, a big belt with a metal buckle, and a pair of black leather trousers. Up until today, a pair of leather trousers is associated with transgression and taboos, but a white shirt is a reassuring object, and it almost annihilates the power of the trousers. The trousers nevertheless shimmer in the light. The shirt is slightly see-through—we can glimpse a white bra beneath it—but has only one button open, not a millimetre of breast for anyone to see.

Her clothes say, look at me my white immaculate shirt and immaculate bra, my bon ton upper body my eyes my hair divided into two precise sections at the center of the scalp I’m going to say something before you can notice my black leather trousers my assertion that can destroy you your world your trembling beliefs but I won’t do it I wore a white white shirt just for you. To camouflage myself in your world, to make you understand me, and make my fierce self understand you, and play by your rules to change them through immanence.